Written by McKell Anderson

While receiving a lovely massage that my husband gifted to me for Valentine’s Day, my therapist began asking me the usual questions:

“Do you have any problem areas?”

“What areas would you like me to focus on most?”

“How do you like your pressure?”

My answer: “Please destroy my shoulders with all the force an invading finger army can deliver.”

So far, pretty normal experience for most aerialists getting a massage. During the massage, the therapist moved to my chronically tight neck and she was surprised with how tense it was.

Masseuse: “Have you been in a car accident recently?”

Me: “No, my neck is usually tight like this.”

Masseuse: “Your neck feels like people I work with that have had whiplash.”

The wheels in my head began to turn with that statement. I was in a car accident when I was seventeen but that was fifteen years ago and I did not experience any severe whiplash from it. However, I commonly let my body gracefully–and sometimes not so gracefully–fall towards the ground until a piece of fabric halts my descent in a rather abrupt manner. The curiosity seed was planted: Can aerial drops give someone a whiplash injury? Has it given me whiplash?

Now, let me start by saying that I’m a firm believer that correlation does not equal causation. Just because things seem to relate, does not mean that it is truth. You should know that despite my supplications to the oracle that is Google, my canoodling on aerial forums asking around, or my general inquiries to my aerial role models, I couldn’t find any existing data on the idea.

Aerial is still a young industry, so having scientific data collected on many practitioners is highly unlikely. Data not existing doesn’t necessarily mean that there isn’t a correlation; it could just be a sign that no one has researched it yet. For the remainder of this post, we will go over what information we DO have on whiplash injuries and aerial drops separately, then compile the information into some helpful guidelines for safe dropping. If you ever come across any research on this topic, I’d love to be the first one you share it with! Much appreciated.

A Crash Course on Whiplash (no pun intended)

“Whiplash is a mechanism of injury due to forceful, rapid back-and-forth movement of the neck, like the cracking of a whip. The energy transfer of the rapid acceleration and deceleration forces to the neck can result in damage to the soft tissue structures of the neck.” -Dr. Emily Scherb

Most of the observations made about whiplash relate very specifically to car accidents. Whiplash injuries are kind of a fickle thing and vary by individual. Some people experience a little pain for a few days but make a full recovery with very little side effects in a short time. Others do not notice any symptoms until many weeks after the accident. The unfortunate thing is that the longer the symptoms persist, the more likely that the damage will become permanent.

Symptoms following a whiplash injury may not be what you would normally anticipate. When you think of whiplash, the normal expectation of symptoms would be tender muscles, limited neck mobility, headaches, and upper back pain. Other symptoms can be a bit sneakier like shoulder pain, anxiety, fatigue, sensitivity to noise, impaired concentration, or temporomandibular joint disorder (TMD/TMJ) resulting in jaw pain.

I’ve observed (and that doesn’t make this a fact) that TMJ pain is more pervasive in the aerial communities I’ve been in than any other groups I’ve associated with. Could be a coincidence but might not be. Only time and data will tell. There are various factors that can increase the likelihood of getting whiplash in an accident. Some of these facts I found interesting when analyzing them with aerial in mind.

- The threshold for soft tissue injury is five miles an hour. Vehicles do NOT need to be going fast to cause the most severe kinds of whiplash.

- Rear end collisions can be the most severe because the torso is the most secured by the seat belt and the neck can move freely. So instead of the entire back being able to absorb the force, most of the energy is transferred to the neck alone.

- Position of the head during the collision is also a critical element for injury severity. If the neck is not in a neutral position, say while you have your head slightly turned to adjust the radio, then the available range of motion is greatly diminished. This will result in the force of the collision being localized to one side of the spine.

- Awareness of impending impact is also a factor. If an individual can brace themselves for the collision then their ability to effectively stabilize during the accident increases. Studies have shown that passengers experience greater whiplash injury than the driver, often because they are less aware of the situation.

Aside from all the potential factors DURING an accident, there are even MORE chances to impact whiplash with the human body. Since no two bodies are identical, here are some of the physical considerations in assessing whiplash risk.

- Muscles, ligaments, and other tissues help absorb shock to the body without causing injury. Individuals that are physically fit and in a good health condition will be more efficient in stabilizing severe forces to the body.

- Strength needs to be balanced on both sides of the body. Uneven muscle development in the back can result in the spine being in a less ideal posture during collisions or unable to stabilize evenly during an accident.

- Body type can put certain individuals at risk. Those that have smaller frames, longer necks, and less supporting muscle mass have an increased risk for whiplash. Women are statistically twice as likely to be injured than their male counterparts.

- Small children can also have a proportionally larger skull in comparison to their neck and less muscle mass to compensate for it, making them prone to injury.

- Older populations also have a great injury risk due to the natural degeneration of human body as it ages. “Ligaments become less pliable, muscles less flexible, and the bones, joins and discs less able to absorb impact without injury.”

- Good body mechanics is also helpful. Individuals that train to have coordinated control over muscles and joints, engaging in the right order with the right tension, will be able to stabilize their body with less mechanical stress and pain.

Drop Mechanics

There seems to be a time in a lot of aerialists’ lives where drops are “the end all, be all” of their hearts desires. While I don’t think this is true myself, my entire third year of practicing aerial was spent consuming all the drops I could get my greedy little hands on. So, I’ve BEEN there and I understand the draw. If drops are what you want, then I hope this will help you understand what to anticipate and make the process as pain free as possible.

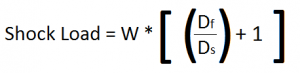

First thing to address, drops cause force! Lots of it. While you might be an aerialist somewhere between 100-200lbs, with the additional forces we add by embracing gravity abruptly, the true force (or shock load) can end up being around 1,000 pounds. A general rule of thumb is that 1,800 pounds of force can cause a person to black out and bleed internally. This should be avoided! HOWEVER, that’s not to say that injuries cannot occur to our persons with less force than that. Let’s look at the shock load formula to help further our discussion:

W = Weight of Aerialist

Df = Distance Falling

Ds = Distance Stopping

In this formula, the most important relationship to pay attention to is the falling and the stopping distance. Since it is a fraction, everything you solve for begins here and SHOULD likewise be what you notice when learning drops. (Who says math and real life don’t intermingle?) If you are falling a large distance and stopping abruptly, you will create larger amounts of force. In aerial, we very often choose to fall large distances on purpose, but if we want to reduce the impact to our bodies we need to pay attention to how we can increase stopping distances to help provide a physical reprieve.

Stopping distance is a hard thing, here are factors that can impact the stopping distance:

The Type of Drop Chosen.

I know, duh. Some drops have more freefall time that happens and others are more of gravity guided unwrapping, think slack drops versus star drops. Drops can also vary on how many wraps will tighten at the end to help slow us down more gradually.

Equipment Choices.

Depending on the apparatus, there are choices an aerialist can make to help the equipment absorb more shock by stretching during impact. Think of high stretch or low stretch aerial silks, bungee packs added to the top of rigging, or ropes with stretch used for pulley systems.

What Part of the Body the Drop Culminates On.

I don’t know about you, but my thigh has a lot more “squish” available than my ankle does. Dropping to meaty regions versus boney regions will have different comfort levels and stopping distances.

FORM!

If you have been waiting for the moment where we address the physical capabilities needed, now is the (first) moment. The human body is made up of muscles, ligaments, and tendons that are great at absorbing shock and impact. This ONLY happens when proper strength and engagement are available. MORE ON THIS LATER!

There are specific instruments that can measure shock load (dynamometer) and these often show the calculated estimation to be higher than reality. Why the discrepancy? Many of the above factors are very dependent on the human body and are not the same from individual to individual. Even in one person, your day-to-day ability to absorb the shock of drops will not be the same. Muscle soreness and stiffness will inhibit your body’s abilities to absorb the shock load of drops.

How to Drop it like it’s Hot (Safely)

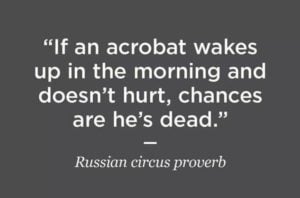

From the discussion so far, we know that whiplash is caused by a rapid extension and flexion. We know that it often happens in accidents of low speeds. We know aerial drops can create a lot of force on the human body. I’m going to go out on a limb and conclude that whiplash in aerial is a real possibility. How often or how severe? I couldn’t accurately guess, but it IS something we need to be mindful of in our practice.

“Incorrectly wrapped or executed drops can result in sprains, whiplash, burns, and broken necks. You don’t get to be cavalier about them. Respect the risk, respect the work, respect the process, respect the community.” – Laura Witwer

Most importantly, based on reviewing this information, I feel that there are easy practices to put in place to help mitigate the risk for whiplash or other injuries while performing drops. Check out the list and let me know if there are more things you would recommend:

1: Strength First, Drops Second

There is a terrible habit in aerial of attempting drops before the body is strong enough to support it. Having the appropriate strength along the spine is a key element in the body being able to execute drops safely and gracefully.

“With any particular drop, an untrained artist would be more likely to have a whiplash type injury than someone who has trained up to that level because the trained performer has more strength and control in their paraspinal musculature and can withstand more force and load.” -Dr. Emily Scherb

Flailing form is usually the result of an aerialist attempting something they aren’t strong enough for and flailing is how we get injured. The lovely and eloquent blogger, Laura Witwer, just wrote a wonderful blog about assessing the readiness of an individual for drops (link at the bottom). Use discernment when deciding to learn aggressive drops and ESPECIALLY when to teach them to others, specifically children with their proportionally large developing domes. They aren’t party tricks friends!

2: Neck Engagement – Embrace the Jabba Chin

One of the factors with whiplash was related to seatbelts restricting torso mobility which resulted in the neck taking more force than desired. If you are engaged in your core for a drop, but your head is loose like a bobble head doll, then your neck is in danger! When executing drops, it is important to have your neck engaged along with the rest of you.

The Jabba Chin is the practice of engaging your neck so that your chin drops and pulls in just enough to feel a little bit of pressure on your windpipe. Your jaw should not be clenched. Don’t give yourself a genuine double or triple chin, because we will still want to look sexy while we do things. Keep your neck position neutral during the drop and wait to fully extend or arch until the end.

3: Train Both Sides

Your bodies ability to absorb shock appropriately depends a lot on having a balanced muscular system. If you constantly only train one side, then your body will lose its ability to evenly react to force and will make you prone to injury during those critical moments. I know some people do not drop on their offside for safety, which is not the point I want to make here. Aerialists need to be able to climb on both sides, invert on both sides, hip key on both sides, meat hook on both side… All your aerial foundations should be as ambidextrous as possible so your body is balanced.

4: Coordinated Engagement Practice

The key to good execution isn’t just tensing all your muscles at once. We need to make sure we are engaging muscles in the correct order and with the right amount of tension, because if we do not it will increase mechanical stress and pain of what we are trying to accomplish. Aerial is hard enough, no need to make it harder by over engaging, like with clenching your jaw for any reason or being too tight when attempting beats.

There could also be a different type of engagement needed for certain things. For some drops, it is important to engage the abdominals by ‘pushing out’ to protect the ribs instead of ‘pulling in’. Practicing drills like scorpion/sacrum falls will give the body a chance to learn how to fall and engage in the appropriate order to make bigger drops easier and more intuitive.

5: When in Doubt, Walk it Out

Pro Tip: The first time you do a drop you should always have doubt. Meaning that the first time you try a drop you need to walk through the exit/drop instead of just going for it. Your body has never done the trick and cannot understand what will happen. Having a method to walk out of a drop is important because it teaches the body what to expect. Being able to anticipate what will happen helps the body engage in the correct way to protect itself. Much like the driver of the car being able to prepare for impact better than the passenger, you need to understand what is coming before you do a drop “full out”. You don’t want to do a drop as a passenger, you need to be the driver. This is even more important if you are attempting a drop that has a direction change, lest your head channel its inner pinball machine.

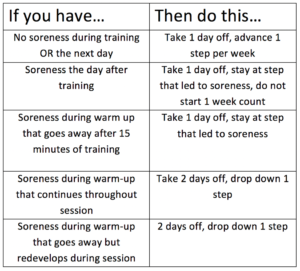

6: Avoid Drops When Sore

Another way the body will lose its ability to absorb shock is when it is fatigued. If you have been overtraining and are sore, then your muscles will not be able to support you like they would on days where you feel like a spry young pup. Save your drops training for the days that your body can handle it safely.

7: Designated Drop Equipment

Where possible, try to have a rigging point set up with equipment that is drop friendly. Put a stretchy fabric up or have a point that has a bungee pack on it. When learning any skill, repetition is key to mastery, but repeating aggressive drops can be daunting and painful. Having a set piece of equipment that helps mitigate the stress when practicing is helpful on the body.

8: Learn Drops with Coaches

While this is not a conclusion being made from the analysis on the whiplash data, this is of equal importance. Recently Brandon Scott, an accomplished aerialist, published a rant on the dangers of learning from Instagram. I really loved what he had to say:

“Drops are the flashiest part of aerial. They are dynamic and exciting, their impact makes them almost necessary for the climax of an act, and when they are done right, they are just plain fun to do!!”

But did you catch that caveat? ‘When they are done RIGHT’. There is a large range of how difficult or technical drops can be. But at any level, drops are part of what makes aerial dangerous. While ‘death defying’ may be used as a descriptor to pull in an audience, we as aerialists need not consider death, let alone defy it, if we have all the information and preparation for safe execution.” -Brandon Scott

Preach Brandon, preach!

Good aerial instructors will give students the information they need to successfully execute a drop without injury. A lot of times success is achieved through a series of progressions that aren’t ever shown during a performance or on an Instagram video.

Drops will forever be a huge part of aerial and they are a wonderful tool, but aerialists need to take the time to learn them safely and appropriately. Hopefully the content of this blog will help you in your endeavors to gain more information and help you do amazing things more safely!

Congratulations! You made it to the end! Share your thoughts below!

Resources:

https://treatmentforwhiplash.com

https://www.lifemark.ca/blog-post/understanding-whiplash

http://www.laurawitwer.com/2018/04/11/pardon-sir-madam-not-ready-drop/