This is a continuation of the previous post about the important of self-practice for students. Blog by McKell Anderson.

3 – Familiarity VS Mastery

Have you ever practiced aerial to a specific playlist? To the point where when one song ends that you know what song is going to play next? Or have you ever read a passage in a book so many times that when you get a few words in that you remember what it is all about? You don’t have it memorized and can’t recite it when the book is closed, but you recognize it.

Recognizing input isn’t the same as learning and is a far cry from Mastery. Often, recognizing what is happening can make us feel like “we already know” something, and the brain turns off. How does this relate to aerial? Have you ever started watching an instructor demonstrate something you are familiar with and stopped paying as close of attention? Or have you done a warm-up or conditioning drill so many times that you think you are a pro, only to have the instructor come around and tell you to zip up your core?

When asked to do the “hip key drill” at the beginning of class, you (or your student) fan kick like a dream with perfect execution. From the ground AND from the air! Later, when lost attempting the sequence in class, the help provided is to “find the hip key again” to restart. This tip is met with wide eyes of confusion, and the instructor must offer step by step instruction to get there successfully. This would be a sign of familiarity with one entry to a hip key, but light years away from the true understanding of the wrap and how it relates to other things.

How does one get beyond familiarity and take the next step to mastery? The book addresses many ways, but one crucial thing is this: stop repeating the same drills over and over again! Mass-practice of the same exercise will not lead to mastery, just like rereading text doesn’t lead to better recall. (I wish I had known that when I was in college.) This creates a familiarity that lets you feel good about your practice when your execution is not improving to the degree that you perceive. This leads to a thought that can be haunting:

Perceiving your practice as having gone well is often a symptom of familiarity and not mastery.

4 – Variety is the Spice of Circus Life

There are things we can do to help prevent ourselves from falling into the trap of familiarity. Learning and practice should involve varied approaches. One of the most significant issues with training is that sometimes we do the SAME drills for the skills we are learning. Lack in variation diminishes our ability to establish extensive connections mentally and physically, which results in a very shallow depth of understanding.

In the book, a study that was done tested a person’s ability to throw a ball into a bucket that was three feet away. The participants were separated into two groups. Group 1 practiced throwing balls into a container that was three feet away, just like the test would require them to do. Group 2 practiced throwing balls into a container at different distances, but never the three-foot distance needed for the test. After the practices, which group performed better on the test? Group 2. Even though the first group was doing the EXACT motion that the test would measure, their execution was not as good as the group with variety in their practice.

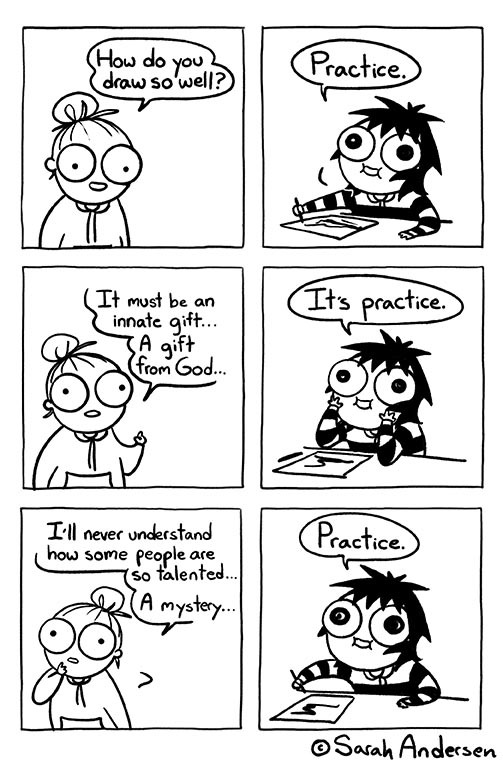

Thanks Sarah Andersen for the comic.

A considerable benefit of variety in training is that it develops problem-solving abilities. For any aerialist that has ever gotten stuck in the air, being able to troubleshoot is an extremely critical skill. If you have learned ten different ways to get into a hip key through variability in training, then the ability to recognize different paths to save yourself in the air is more readily at hand and in the muscle memory of the body.

This past summer I participated in the Born To Fly Teacher Training for Level 1 Silks. The week of training was very intense and sometimes a bit overwhelming. I remember us going over invert progressions for HOURS. There was a list of different drills that boggled my mind, and at the time I thought, “Do we REALLY need to do all of these?” However, when I read the section in Make It Stick about the importance of variety, I realized those invert drills are not meant to all be done together when learning how to invert but are a benefit in providing different ways to do similar things over time. The various exercises doled out bit by bit will benefit an aerialist more than the same four drills done during warm up every single week when it comes to developing inversion strength.

Some subconscious repetition I have seen with training happens when you choose where in the room you like to train and what apparatus to use. In a class, students often find their way to a specific spot in the room and never leave it. Even though six apparatuses are hanging, they never leave THE ONE. Different environmental spacing and different equipment help develop better skills. Another example from the book was when a hockey team started performing their passing drills on different areas of the ice rink in practice, and the overall cohesiveness in the gameplay improved. It seems like a no-brainer, but when we practice, we tend to all congregate to the same area we usually do. Change which points you train on in the room, try the stretchy fabric, the braided rope, the big 38” lyra, or the un-taped trapeze bar. The difference in how things feel is vital to learn.

Variety in timing is also a great tool. Not only does this help with spaced retrieval for better learning, but this also helps with execution at different energy levels. Do you always train hard skills at the beginning of practice? Just after warm up? If you only condition how to do inverts at the beginning of class, then what will happen when you need to execute one at the end of a difficult routine when your body is VERY fatigued? Choosing different times during your practice to try skills can help make you into the best aerialist you can be. Don’t be afraid to do conditioning at the end of class or training.

Open Gym Practice is a Must

To get better at anything in life, practice is a key component. We now know that what happens in class is not “practice.” That is the time that new information is going in. We need time for the brain to process and assimilate that information in our minds. After our lesson, we need to get up in the air again later to review. For a lot of aerial students, aside from the weekly classes, not much additional practice happens. This approach removes the element needed for the recall of the things done in class to make them a more permanent part of a student’s repertoire.

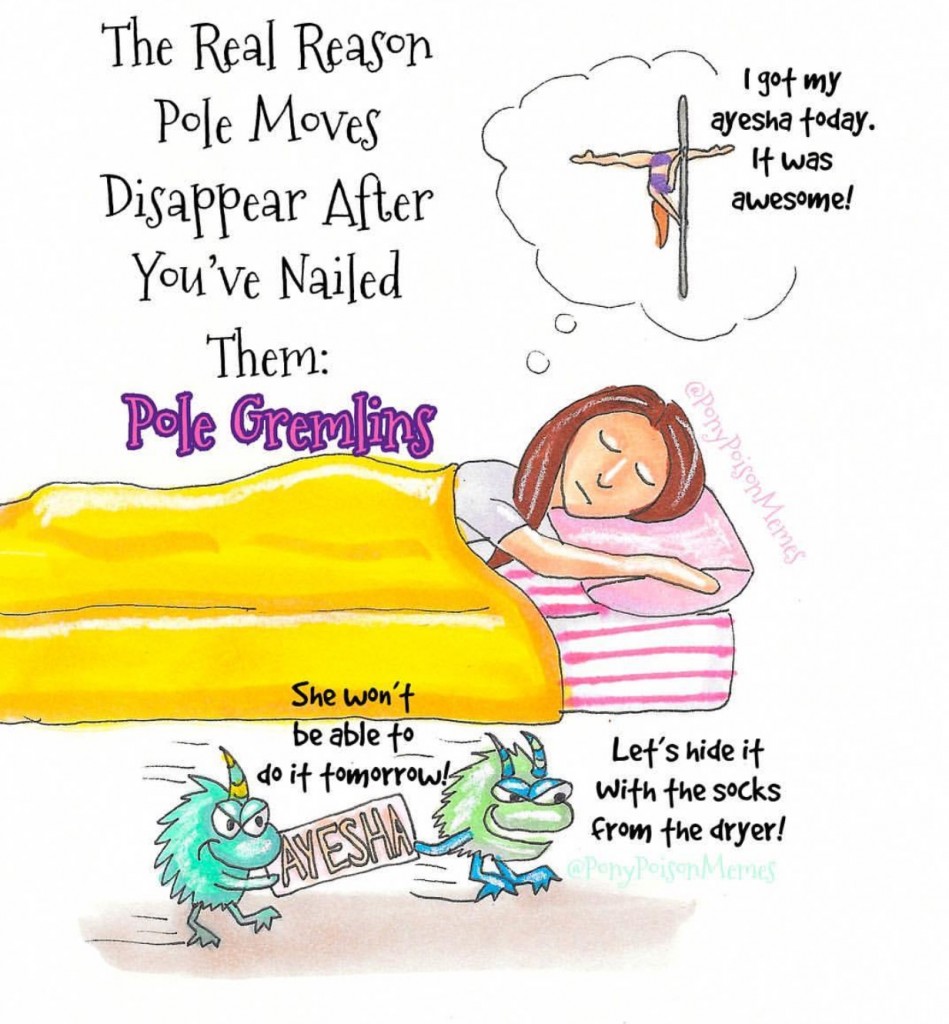

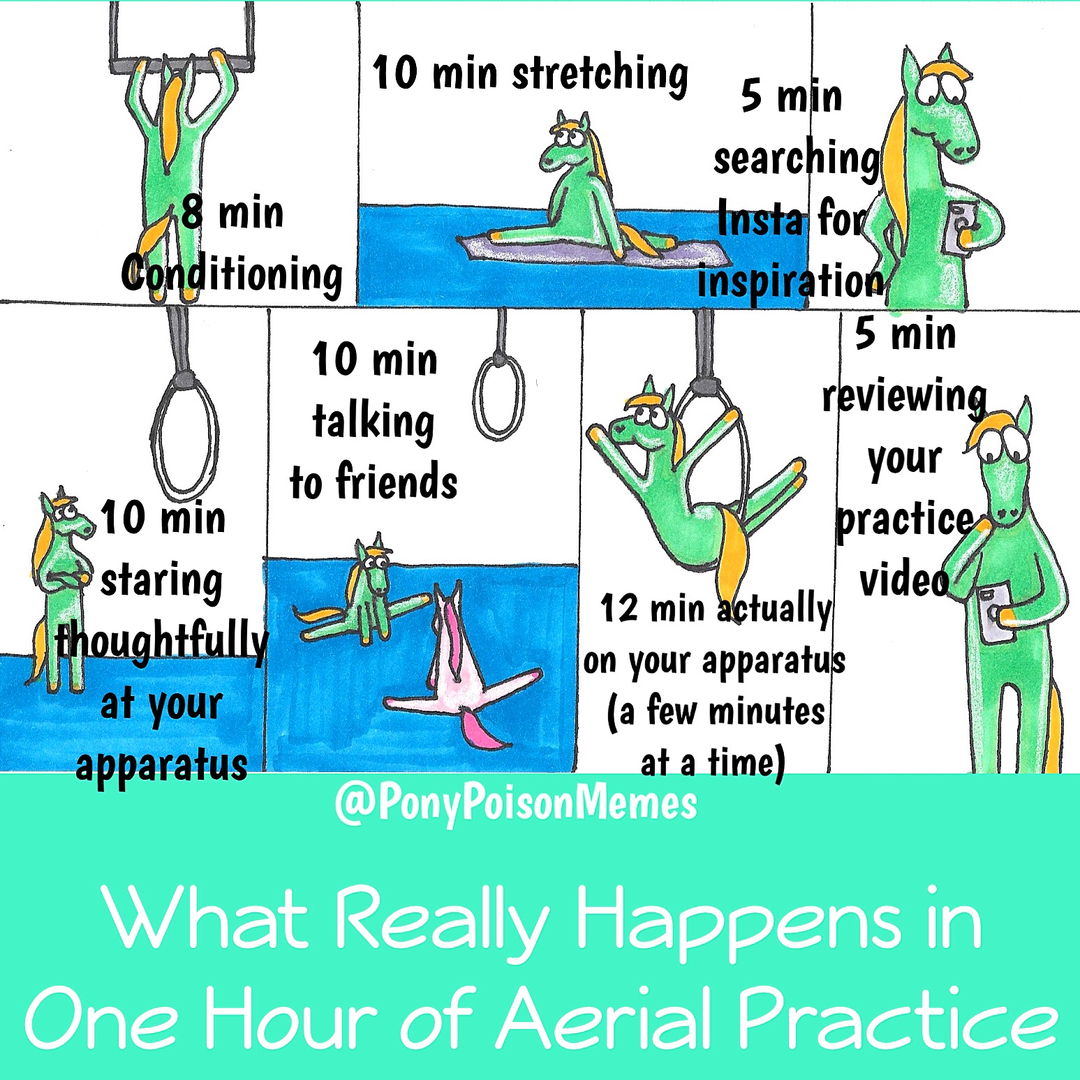

Thanks Pony Poison for the comic.

If the studio you attend has an open gym, make sure you take the time to participate regularly. This is the time to get the things out of your head and truly learn them. Practicing A LOT is not as important as practicing effectively. Here are some tips for effective good open gym practices:

1. Do not train alone for safety and helpful group problem-solving.

2. Make open gym training follow a different pattern than standard class structure.

3. Try different conditioning exercises or try them on a new apparatus.

4. Don’t forget about your “other side.”

5. Choose to review skills that are not fresh in your mind and harder to recall.

6. Review any forgotten things low and slow before moving up.

7. Try to connect skills, even if you fail.

8. Let yourself get frustrated, but don’t fall apart over it.

9. Do not let someone teach you something new; this is remembering time!

10. Write down any questions or things you couldn’t figure out for your instructor.

To clarify, I don’t think there is anything wrong with skill sharing (item #9), but that when it comes to learning retention, using open gym for skill sharing undermines our goal. The whole point is to add training time around the need for retrieval of skills without an instructor there to make it too easy. Plan additional training opportunities for skill sharing.

For studios and instructors, open gym is often a sensitive topic. Rules need to be established to make this type of practice a safe environment and not a liability risk. Here are some suggestions for ensuring that happens:

1. Have staff members present for supervision and emergencies, not instruction.

2. Require crash pad use for all apparatuses in open gym.

3. Wait to lower in equipment (or however your studio brings them out) until after enough time or warm up has elapsed.

4. Create a designated cell phone area that is not directly next to an apparatus but close enough for filming.

5. Display a list of any open gym restricted skills.

6. Provide “open gym homework” during regular weekly classes.

7. Ensure class time incorporates training on troubleshooting when stuck.

8. Pull apparatuses up (or however your studio puts them away) before open gym is over to provide cool down time without aerial temptations.

Many of these things are commonly part of studio open gym rules. I would encourage studios to designate a cell phone area for the sake that watching a video and immediately hopping onto an apparatus to do it isn’t a long-term learning skill. The student should have at least a little walk to forget and must recall the video content. Also, it is appropriate to decide dangerous skills are too risky for open practice environments without the appropriate instructor. Teachers providing homework can help encourage open gym attendance.

While taking time to practice skills away from an instructor can be scary and overwhelming, for the teacher as much as the student, studies show this learning strategy is sound. Ensure your learning methods are prepared to support a way for information to go into your mind and a way of getting that information back out. Without this balance, the frustration of forgetting will be your enemy instead of your guide.

McKell Anderson is currently working as Rebekah Leach’s right hand woman, creating blogs, fun newsletters, photo editing, and doing all the good stuff to make this curriculum project an aerial dream-come-true.