A 2-part blog by McKell Anderson.

When it comes to the aerial and circus industry, there is a giant push for safety, which is terrific! A big thing that has come up is training without an instructor is not a safe practice, specifically when attempting to learn things from the interweb. While I agree that having a qualified coach is essential to a safe aerial career, I think we place too little emphasis on the importance of practicing aerial WITHOUT your instructor.

Wait… What?!

Is she suggesting that we let beginning aerialists do ANYTHING unsupervised?! That is crazy! Unacceptable! This is nonsense! People are going to DIE!

Take a deep breath, stay calm, and read all the way to the end before you write this off as rubbish.

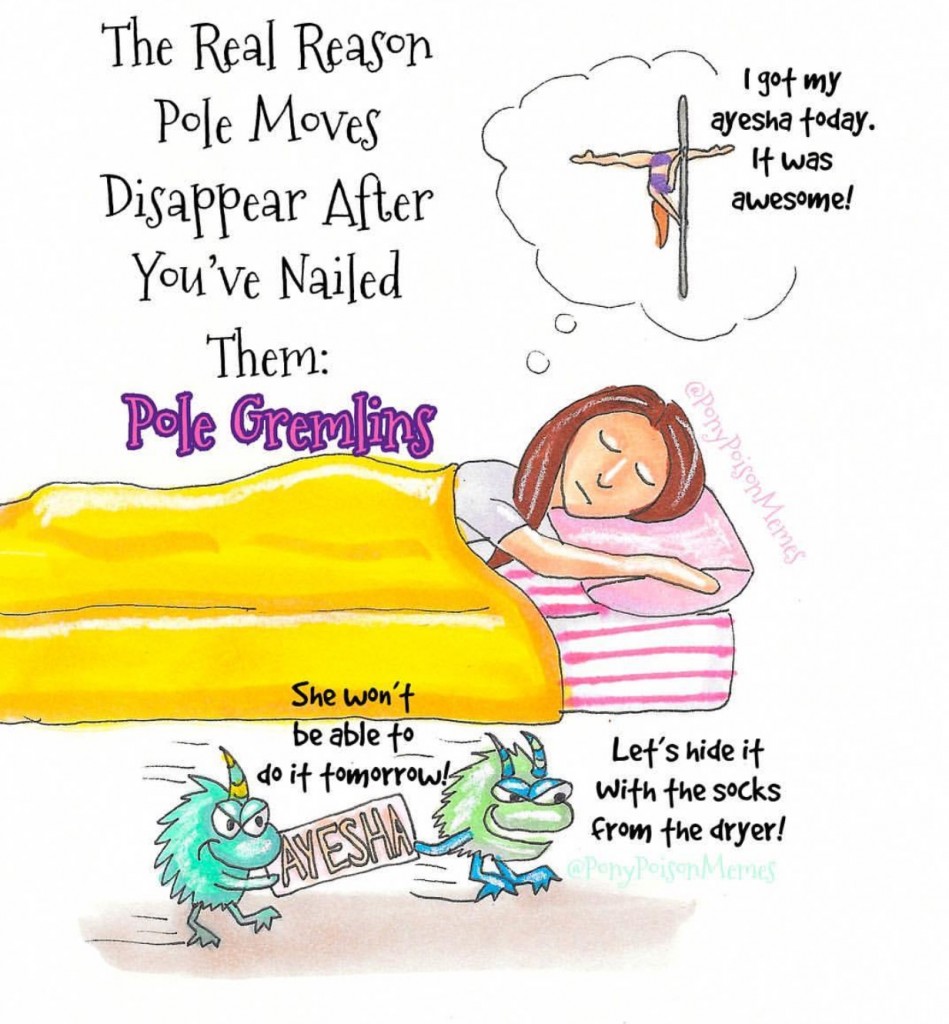

Have you ever had a student (or are you the student) that can execute 90% of what has been taught in class, but then has the memory of a goldfish when asked to perform a skill weeks later? Or have you ever sent an instructor a video saying, “Can we learn this in class pretty please?!” to get a reply from your kind, patient, wonderful instructor saying, “We have done this skill at least a dozen times in class before.” There is a vast difference between learning skills in class and remembering them later. I think this is a particularly common issue with complicated wraps used in more advanced skills.

This phenomenon is not unique to aerials. There is actual research to why stuff falls out of our brains and what we can do to prevent it. In Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning, Peter Brown, Henry Roediger III, and Mark McDaniel shed new light on how learning works from a variety of empirical studies done over the past decade.

SPOILER: People think they are learning and retaining well when they are not.

Going through this book has completely changed my approach to learning and teaching. If you do not have time to read it on your own, here are a few of the nuggets of wisdom that apply to aerial practice.

1. The true direction of learning

2. The importance of the struggle

3. The difference between content familiarity and subject mastery

4. The importance of practice variations

1 – Better Out than In!

“The single biggest idea is that we tend to focus on trying to get new learning into the brain and we do that through repetitive reading and practice. But what research tells us is that learning really happens when we try to get new knowledge and skills out of the brain.” – Make It Stick

Qualified coaches are the best source for putting good aerial knowledge into students’ heads through lesson plans, spotting, and supervised execution. The knowledge going into the brain, while an irrevocably important part of the process, is not where learning happens. Without a situation for an individual to recall the data input and turn it back into the output, long-term retention of learning does NOT occur. If you spend three hours on Instagram watching videos, but never get up and try any of them, did you learn anything from all your aerial research endeavors? In this information age in which we live, getting information into our heads is all too easy. The learning is in the retrieval of the information you took in. You would have to watch it AND DO it.

Doesn’t doing things in class count as learning?

The short answer: No. Why not? Our in-class time is a valuable opportunity for exposure to new information but without strategic lesson design, not the place for retrieval. You recall the information too close to when it was learned. Timing is essential, and there has not been enough time for it to be moved from short-term storage in the brain to long-term storage in the brain. There needs to be enough time for the information to be processed in your fantastic head. The consolidation of new information can result in varying levels of remembering, and the ability to recall skills from long-term storage is the place where learning happens. As an aerialist you need to attend class, take in the lesson and try the skills with your instructor, sleep on it, forget it a bit, then TRY IT AGAIN to maximize learning.

2 – All Aboard the Struggle Bus!

One of the side effects of waiting long enough to forget before practicing a skill again is that it makes it hard. The longer the time that elapses, the harder it gets usually. Wait too long, and you must start all over with the data input. Unfortunately, the struggle is the process that produces the benefit you want.

“It’s a funny thing, but we, especially those of us who are in the teaching profession, think that the more clear and simple we can make new knowledge, the better it’ll be learned and remembered. As learners, when it’s clear, we think, boy, that’s great. I get that.

“In fact it’s the opposite that is true, that when you have to struggle with the new knowledge a little bit, if you hear a lecture that’s very clear but it goes in a different sequence than the text you read, and you have to think about how to reconcile those — that way of engaging with the material enables you to get it to stick.” – Make It Stick

This is a difficult concept for me to swallow because of who I am as a person. I LOVE mapping things out in clear, concise ways. When a progression is organized linearly I get a satisfaction that I cannot describe! When teaching, I love having a lesson planned that sensibly guides students to their destination with as much ease as possible. I do not want them to get discouraged, be upset, or get confused. If I see a student struggling, I try to immediately step in to help. I want it to be simple, and the idea that I have been shortchanging students by making it TOO easy is giving me an identity crisis. I want students to succeed; however, short-term success can come at the expense of long-term learning.

Why is struggling important? This is where the book got very detailed into the functions of the brain, which I will botch if I try to break it down. The central concept describes how the brain retrieves memories and ideas. When we struggle and take the time to pull things out of deep forgotten places, it changes where and how the brain stores those ideas. When I thought about the aerial concepts that I understand like the back of my hand, I realized it was because I sat down and mapped out the theory on my own. I was given the pieces, but by assimilating them into the big picture is what embedded those concepts. This never resulted in my crying in class because it was hard, but the struggle of connecting things outside of class drove them into my mind forever.

Embrace the struggle. If you are in class learning a new skill, try to connect it to other things you know. Try to create relationships in the information that are not being PROVIDED for you. If you are a teacher, make a lesson plan that includes areas where students have to problem solve or remember. Since reading the book, I have made a habit of making students do what was taught the previous week without me saying or showing it again. This action alone has resulted in considerable improvements in student skill retention from week to week. The first week I tried it, it was ROUGH. It took almost ten minutes of precious class time for students to remember the full sequence. During the discussion, I wanted to jump up and show it to them quickly about a hundred times. The process of them figuring it out made it a sequence they haven’t forgotten since that recall exercise.

I made it through my identity crisis, but it wasn’t by abandoning all the lesson plans or careful progressions. I still use those when I teach and try to construct those as I learn. To facilitate more effortful learning, I now try to create opportunities for problem-solving. Sometimes I will show the final pose and give the class time to try and find different ways there, make them create a way to mimic it on the ground, or with a partner. Simple difficulty can be added by having them ask you questions about the skill WITHOUT actually speaking. Now I use my structure to show clear steps, but only after encouraging opportunities to make connections first. When the answers are provided after, the ‘AHA!’ seems a bit more resonant.

There is most definitely a balance between beneficial struggle and leaving class in tears. I challenge all aerialists to make sure that each practice involves a chunk of time where a battle is felt to a reasonable degree. Try a new way to get into something, even if it doesn’t work. Embrace frustration as your long-term learning companion.

Keep reading on our next blog post for points 3 & 4.

7,650 thoughts on “The Importance of Groping in the Dark: Part I”