As aerialists, or just movement artists in general, it is important to take care of our body in order to insure longevity and safe practices. It is common in many other intense sports to burn out well before the age of 30. But in aerial, it is more common to start after 30! This is very unique in the world of movement and I strongly believe it is due to our focus on self preservation and longevity. Therefore, we should make sure to always include some sort of conditioning, flexibility, or cross training for the main joints and muscles that are used in aerial dance. A muscle that is of particular importance for aerialists is the latissimus dorsi, or commonly known as the lats. Dr. Jennifer Crane from Cirque Physio helps us to understand how to care for our lats in this blog post.

What are the Lats?

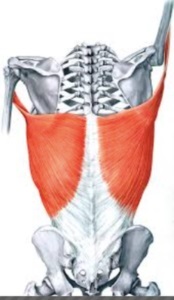

The lats are a huge muscle that affect many different regions of our bodies. Here are all of the different parts of the back and hips that the lats attach to:

- Back of all the vertebrae- from mid back to our sacrum (T7-L5, and sacrum)

- Lower part of shoulder blade (inferior angle of scapula)

- Lower three or four ribs

From these attachment points, they course under your armpit and attach on the top part of your upper arm (intertubercular groove of the humerus). Yep…that’s a big muscle. Because our lats attach to so many different structures, they also influence way more than just the shoulder.

How Can we Measure the Flexibility of Our Lats?

An easy way to measure lat flexibility starts with: sitting with your back to the wall, scoot feet forward and flatten your entire back completely against the wall. Engage abs to keep ribs in. From here, raise one arm in front of you slowly as far as you can, with your palm facing up and your elbow straight. Use your other hand to monitor the point at which your back comes off the wall or the point at which your palm starts to turn inwards instead of staying u. Take a photo of this point. This is your functional lat muscle length.

While not all cases are the same, I recommend at least an angle of 180 degrees of active range of motion. However, the best way to determine your specific needs and goals is to obviously see a sports medicine provider- there isn’t a one size fits all answer!

How Do We Improve Muscle Flexibility in General?

There are three main categories of flexibility, being: passive flexibility, active flexibility, and end-range control. The best way to go about increasing flexibility is by following this warm up/training regimine:

- 10 minutes of cardio.

- Soft tissue prep: spend some time using a foam roller, lacrosse ball, or peanut to address the muscle group that is about to be stretched.

- Passive stretch. Whenever I do passive stretching, I always integrate a contract-relax component to the stretch.

- Active flexibility. I like to take the muscle through a full range of motion into end range of motion, usually with resistance via a weight or a theraband.

- End range control. With end range control exercises, I will typically start by only focusing on activating the antagonist muscles in the last 10-20 degrees of active range of motion of that joint.

What about Flexibility Exercises Pertaining to Lats?

-

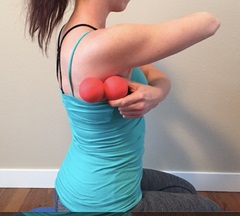

Peanut Mobilization: Lats

Start lying halfway between on your side and on your back, with the peanut placed as shown below. First, move from internal to external rotation with your shoulder just below 90 degrees. Then, move from bent arm to straight arm overhead. This often takes some peanut-adjustment to find the appropriate spot, so if you’re not feeling the “hurts so good” muscle release, move the peanut back a little or down a little. I suggest 10 repetitions per position, per arm, for the best effect.

-

External Rotation-Biased Lat Stretch

Start in child’s pose with elbows shoulder width apart on the bench, and yoga block in hands. Let chest sink, hold 10-15 seconds. PNF contract-relax: gently push your elbows down into the bench while squeezing the ball/block. Hold for 8-10 seconds, then relax and stretch slightly further. Focus on keeping your ribs in during this whole stretch. If you let your ribs splay out, you’re allowing spinal extension, which is one of the most common compensations during lat stretching, and significantly decreases the effectiveness of this exercise. If you feel a pinching sensation in the front of your shoulders, back off the stretch and widen your elbows. If it persists, stop.

-

Modified Dead Bug for Active Shoulder Flexibility

Start with a theraband or tubing around stall bars (or similar). Hold the ends of the theraband with your thumbs pointing up. First, engage your abs and focus on keeping your ribs in for the whole exercise. Bring your arms overhead, while you simultaneously lower one leg. Bring your arms only as far overhead as you can while keeping your lower back flat on the floor. Return to the start position and switch legs. You absolutely must breathe during this exercise. If you hold your breath, you substitute by using your diaphragm instead of your abs for the core strength component. Keep your ribs in and your lower back flat on the mat the whole time. The second you start to arch your back, it is no longer an active lat stretch.

-

Child’s Pose Shoulder Elevation for End-Range Control

Start in child’s pose with your thumbs up. With one arm, first engage shoulder elevators by shrugging your shoulder up slightly. From here, lift your arm up as far off the floor as you can. It may not be very far, but that’s okay! Focus on engaging the muscles around your shoulder blade to start to maintain end range position. Hold this end range position for 5-10 seconds, then switch. This should also be done 2-3 times to fatigue.

A big thanks to Jenn Crane for providing all of the material for this blog post! Dr. Jennifer Crane is a physical therapist, athletic trainer, board certified orthopedic specialist, and published author. She has been a sports medicine professional for eleven years, and has worked with a wide variety of athletes and performing artists throughout that time. In 2015, she worked as a physiotherapist living in China with the Chinese Olympic Teams in preparation for the Rio 2016 Olympics. Now, in addition to maintaining her practice in California, she works on a contractual basis with Cirque Du Soleil, as a physiotherapist in their performance medicine department. You can visit her website here – cirquephysio.com. I would highly recommend checking out her MyFLEX program if you’re looking to improve your flexibility!